Social engineering is a form of manipulation that targets human behavior rather than technical systems. Instead of exploiting software vulnerabilities, attackers exploit trust, fear, authority, and urgency to persuade individuals into revealing sensitive information or performing harmful actions.

This human-centered attack model is a recurring element across many modern cyber threats and is closely connected to patterns analyzed in Online Scams & Digital Fraud: How to Spot, Avoid, and Recover (2026 Guide), where psychological pressure often replaces technical intrusion.

Quick Navigation

How Social Engineering Attacks Work

Social engineering attacks rely on deception combined with carefully chosen context. Attackers study their targets, identify trust relationships, and craft scenarios that appear legitimate or urgent.

These methods align with broader human-based cyber attacks, where repeated exposure and emotional triggers gradually lower a victim’s resistance rather than forcing immediate compliance.

Common Targets of Social Engineering

Attackers rarely choose targets at random. Employees and executives are frequently targeted because access to internal systems can be leveraged for larger breaches. Individuals are targeted for identity theft, financial fraud, or account takeover. Organizations are exploited through procedural weaknesses rather than technical flaws.

This targeting strategy reflects weaknesses in behavioral security rather than infrastructure, a gap often discussed in comprehensive social engineering protection strategies.

Common Social Engineering Techniques

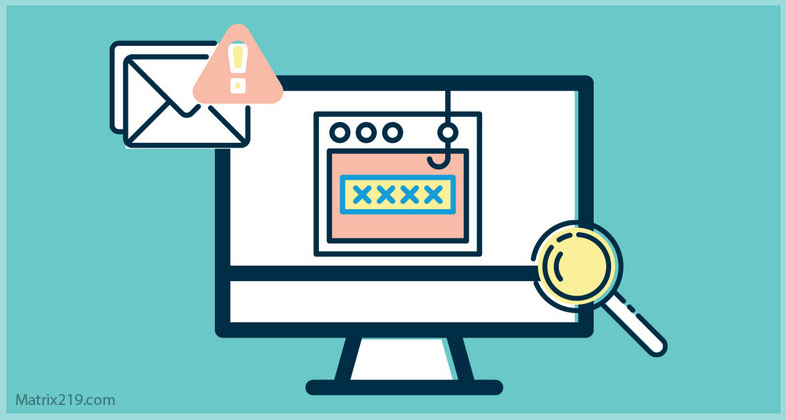

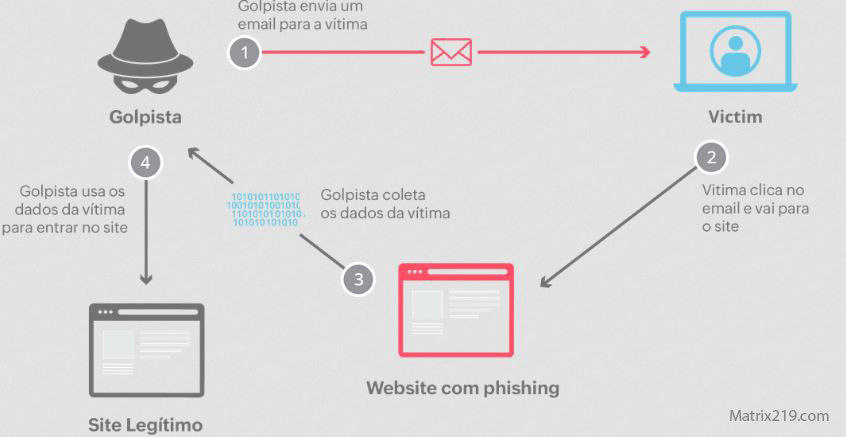

Phishing and Email-Based Scams

Phishing remains one of the most effective social engineering techniques. Fraudulent emails impersonate banks, government agencies, or trusted contacts to extract credentials, payment details, or confidential data.

These attacks frequently escalate into payment fraud scenarios similar to those described in Payment Scams and Irreversible Transfers, where urgency is used to bypass verification.

Pretexting and False Authority

Pretexting involves creating a believable story to justify a request for information. Attackers may pose as IT staff, managers, or service providers to gain compliance.

This technique is particularly effective in environments where procedural trust is high and verification steps are informal.

Baiting and Fake Free Offers

Baiting relies on curiosity or reward. Free downloads, giveaways, or exclusive access are used to trick users into installing malware or surrendering credentials.

These tactics often intersect with automated persuasion methods explored in AI-driven social manipulation, where scale and repetition increase effectiveness.

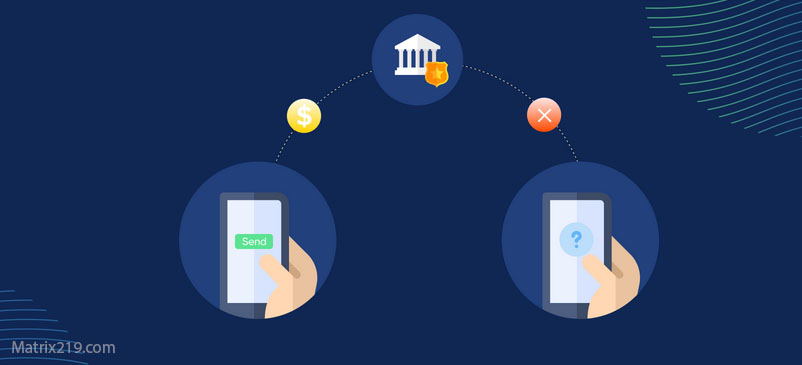

Vishing and Voice-Based Attacks

Voice phishing, or vishing, uses phone calls to impersonate trusted authorities. Victims are pressured into revealing PINs, verification codes, or account details under the guise of security checks.

The effectiveness of vishing demonstrates how authority and urgency can override rational caution.

Physical Social Engineering and Tailgating

Not all social engineering is digital. Tailgating attacks exploit physical trust by following authorized individuals into restricted areas or impersonating staff or delivery personnel.

These attacks bypass technical controls entirely by exploiting human courtesy.

Risks and Consequences of Social Engineering

Successful social engineering attacks can lead to account compromise, financial loss, data breaches, and long-term reputational damage. Once access is granted voluntarily, recovery becomes difficult and often depends on processes similar to those outlined in Account Security and Recovery – How to Recover Hacked Accounts Legally.

The damage is often amplified because victims may not realize they were manipulated until after irreversible actions are taken.

How to Protect Yourself from Social Engineering

Effective protection against social engineering depends on behavioral safeguards rather than tools alone. Verification of requests, independent confirmation channels, and skepticism toward urgency significantly reduce risk.

These defensive principles mirror those applied in Digital Privacy and Online Tracking: How You’re Tracked Online and How to Protect Yourself (2026 Guide), where awareness is the primary line of defense.

Social Engineering in the Modern Threat Landscape

Social engineering remains effective because it adapts to human behavior rather than technology. As platforms automate trust and personalize interactions, attackers increasingly exploit social context rather than vulnerabilities.

Understanding these techniques is essential not only for personal security but for organizational resilience.

Conclusion

Social engineering exploits predictable human behavior to bypass technical defenses. By recognizing manipulation patterns, questioning urgency, and applying consistent verification rules, individuals and organizations can significantly reduce their exposure.

For official guidance on recognizing and reporting social engineering–based fraud, consult Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – Avoid Scams and Fraud.