Social engineering techniques focus on exploiting human behavior rather than breaking technical systems. Instead of attacking software directly, attackers manipulate trust, authority, curiosity, or fear to gain access to sensitive information, financial assets, or protected environments.

These techniques represent a core pillar of modern cybercrime and are foundational to the broader threat models explained in Social Engineering: The Complete Guide to Human-Based Cyber Attacks (2026).

Quick Navigation

Why Social Engineering Remains Effective

Unlike technical exploits, social engineering adapts to context. Attackers observe routines, communication styles, and organizational hierarchies, then design interactions that feel familiar or urgent.

This adaptability explains why many large-scale incidents escalate into scenarios covered in Online Scams & Digital Fraud: How to Spot, Avoid, and Recover (2026 Guide), where human decisions—not system failures—become the entry point.

Phishing and Email-Based Manipulation

Phishing is the most common social engineering technique. Attackers send emails or messages that impersonate trusted organizations, prompting victims to click malicious links or disclose credentials.

Phishing attacks often act as the first step in larger fraud chains that later transition into Payment Scams and Irreversible Transfers, where urgency removes the opportunity for verification.

Targeted Attacks: Spear Phishing and Impersonation

Spear phishing focuses on specific individuals or departments using personal or organizational details to increase credibility. Attackers may pose as executives, IT staff, or business partners to extract sensitive information.

These targeted approaches rely on the same trust automation weaknesses explored in AI-driven social manipulation, where personalization amplifies perceived legitimacy.

Voice and SMS-Based Social Engineering

Vishing (voice phishing) and smishing (SMS phishing) exploit real-time communication. Phone calls and text messages create pressure by demanding immediate action, often framed as security incidents or account problems.

Because these channels bypass traditional email filtering, they frequently succeed where automated defenses fail.

Physical Social Engineering and Environmental Exploits

Not all social engineering is digital. Physical attacks involve impersonation, tailgating, or exploiting unsecured workspaces to gain access to systems or documents.

These methods bypass technical controls entirely by exploiting procedural gaps, reinforcing why comprehensive social engineering protection strategies emphasize process design over tools alone.

Social Media Exploitation and Reconnaissance

Attackers routinely mine social media platforms for personal details, work roles, relationships, and routines. This information is used to craft believable scenarios that lower suspicion.

Such reconnaissance mirrors risks discussed in Digital Privacy and Online Tracking: How You’re Tracked Online and How to Protect Yourself (2026 Guide), where oversharing directly increases attack surface.

Baiting and Curiosity-Based Attacks

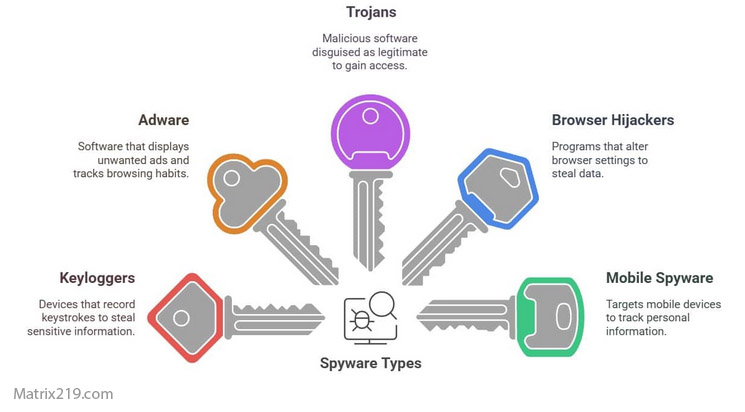

Baiting relies on curiosity or incentive. Free downloads, giveaways, or abandoned storage devices are used to lure victims into interacting with malicious content.

Once engagement occurs, attackers often escalate toward credential theft or malware deployment.

Pretexting and Fabricated Scenarios

Pretexting involves creating a detailed, believable story to justify a request for information. Attackers may claim to be auditors, researchers, or internal staff performing routine checks.

These fabricated scenarios succeed because they exploit assumptions of legitimacy rather than technical weaknesses.

Organizational Impact of Social Engineering

Successful social engineering attacks can lead to account compromise, financial loss, data exposure, and long-term reputational damage. Recovery often depends on processes similar to those outlined in Account Security and Recovery – How to Recover Hacked Accounts Legally, where speed and documentation become critical.

How Individuals and Organizations Can Reduce Risk

Effective defense against social engineering is behavioral and procedural. Key safeguards include independent verification, restricted information sharing, clear escalation paths, and ongoing awareness training.

Technology can support these controls, but it cannot replace disciplined human judgment.

Conclusion

Social engineering techniques exploit predictable human behavior rather than technical flaws. As attackers refine manipulation methods, awareness, verification, and structured processes remain the most reliable defenses.

Understanding how these techniques operate is essential for reducing risk across both personal and organizational environments.

For official guidance on recognizing and reporting social engineering–based fraud, refer to Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – Avoid Scams and Fraud.