Who is responsible when critical infrastructure fails is a question that surfaces immediately after major outages, blackouts, or service disruptions. Public attention often focuses on finding a single party to blame, but responsibility in infrastructure failures is rarely simple or singular.

Critical infrastructure operates through layered systems involving operators, vendors, regulators, and government oversight. Failures usually emerge from a chain of technical, organizational, and policy decisions made over time. This article explains how responsibility is assessed, why accountability is complex, and how misattribution can undermine recovery and resilience.

Quick Navigation

Why Responsibility Is Rarely Clear-Cut

Infrastructure systems are not owned or operated in isolation.

Responsibility may be distributed across:

-

Infrastructure operators

-

Technology vendors

-

Maintenance contractors

-

Regulatory authorities

This complexity increases exposure to critical infrastructure cybersecurity risks and makes single-point blame misleading.

Operator Responsibility: Day-to-Day Control

Infrastructure operators are responsible for:

-

Safe system operation

-

Maintenance and monitoring

-

Incident response execution

Failures may stem from:

-

Deferred maintenance

-

Inadequate training

-

Poor operational procedures

However, operators often work within constraints imposed by aging systems and limited budgets.

Vendor Responsibility: Technology and Support

Vendors influence reliability through:

-

System design choices

-

Patch availability

-

Security support lifecycles

In environments affected by industrial control system security failures vendors may no longer support deployed technologies, limiting operators’ ability to remediate known issues.

The Role of Regulators and Oversight Bodies

Regulators shape infrastructure resilience by:

-

Setting safety and security standards

-

Approving investment plans

-

Enforcing compliance requirements

Regulatory gaps or outdated standards can allow systemic weaknesses to persist unchecked.

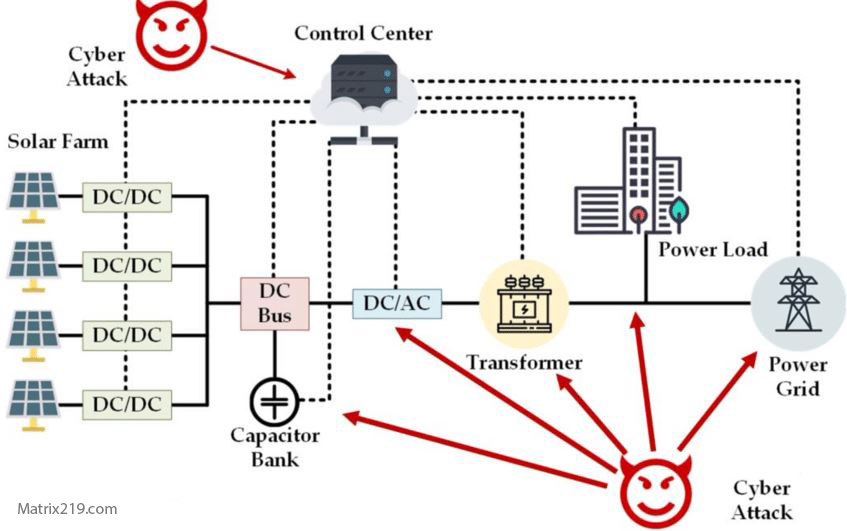

Shared Responsibility in Cyber-Related Incidents

When cyber activity is involved, responsibility becomes even more complex.

Key questions include:

-

Were known vulnerabilities ignored?

-

Were access controls sufficient?

-

Were monitoring and response capabilities adequate?

These assessments often overlap with cyberattack attribution challenges and take time to resolve.

Distinguishing Failure From Negligence

Not all failures imply negligence.

Investigators differentiate between:

-

Unavoidable technical failure

-

Reasonable risk accepted under constraints

-

Preventable issues ignored despite warnings

This distinction is essential to fairly assign responsibility and aligns with power grid failure vs cyberattack analysis principles.

Government Responsibility in National Infrastructure

Governments play a role by:

-

Funding modernization efforts

-

Defining national security priorities

-

Coordinating cross-sector response

When infrastructure remains outdated, questions arise about long-term policy decisions rather than immediate operational errors.

who is responsible when critical infrastructure fails

Why Premature Blame Is Dangerous

Rushing to assign responsibility can:

-

Obscure root causes

-

Discourage transparent reporting

-

Shift focus away from systemic fixes

This dynamic is common in politically sensitive incidents linked to state-sponsored cyber operations explained narratives.

Accountability After the Incident

Post-incident accountability may involve:

-

Regulatory investigations

-

Contractual reviews with vendors

-

Policy and funding adjustments

True accountability focuses on preventing recurrence, not just assigning fault.

Building Responsibility Into Resilience

Resilient infrastructure requires:

-

Clear ownership of risks

-

Defined decision-making authority

-

Transparent reporting mechanisms

These elements are integral to critical infrastructure cyber defense strategies and long-term system stability.

Conclusion

Responsibility when critical infrastructure fails is rarely singular or immediate. Failures reflect cumulative decisions across technology, operations, and governance over many years.

Understanding shared responsibility helps move discussions away from blame and toward meaningful improvement. In critical systems, accountability is most effective when it strengthens resilience rather than satisfying short-term narratives.